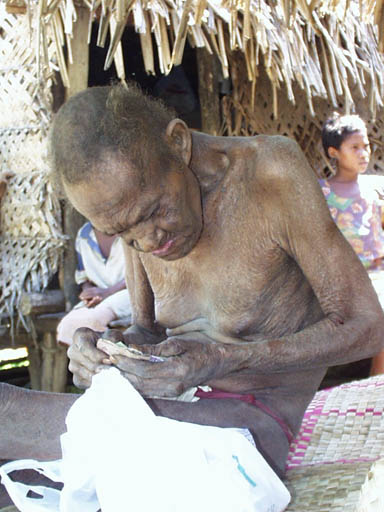

Tolosi: Story-teller to generations of seekers, an an informant of Baldwin, Leach, Digim'Rina, Darrah and most likely many more. Tolosi was invaluable to Trobriand scholars in the later half of the 20th century.

Boyowan [1](Trobriand) Oral Literature

The importance of utterances from the past is reinforced by beliefs that the welfare of the living is directly in the hands of ‘those who spoke before’ and who take an active interest in the adherence to values laid down in the past by the living

Allan C. Darrah

DEPTH Project

The majority of recorded and translated Trobriand oral literature has been a well-kept secret. Malinowski included a number of myths, many spells and a few folk tales in his numerous publications. Happily these limited offerings were greatly augmented by heretofore unpublished major collections of stories and myths collected first by Father Bernard Baldwin in the late 1930's and then by Jerry Leach in the early 1970's. The Boyowan transcriptions and English translations of the Baldwin and Leach collections are now available on this website.[2] The Baldwin collection consists of a manuscript, written by Baldwin, which incorporates dozens of English translations of the Boyowan stories and myths he collected, as well as separate PDF file of their transcriptions in Boyowan.[3] The Leach collection contains approximately three hundred narrative transcriptions with translations provided by Leach’s Trobriand students at the University of Papua New Guinea.[4] Although both collections lack examples from two of the five genres found in Boyowan oral literature, magical spells (yopa) and songs (wosi), together they still preserve a treasure trove of Trobriand heritage.

Genre of Literature:

As in most things Trobriand, Malinowski provides a jumping-off point for classifying Trobriand oral expressions:

"First of all, there is what the natives call libogwo, 'old talk', but what we would call

tradition; secondly, Kukwanebu, fairy tales, recited for amusement, at definite seasons;

thirdly, wosi, the various songs and vinavina, ditties, chanted at play or under special

circumstances; and last, not least, megwa or yopa, the magical spells. All these classes are

strictly distinguished from one another by name, function, social setting, and by certain

formal characteristics." (1922: 299).

Malinowski’s assertions about the clarity of distinctions made between various genres of expressions has been challenged by Jerry Leach. In Imdeduya: A Kula Folktale from Kiriwina Leach points to the many inconsistencies and contradictions to be found in Malinowski’s various treatments of Trobriand oral literature.

Malinowski has, in my opinion, presented an incomplete and internally contradictory

account of spoken narrative information sets of 'stories'. In doing so, he has not followed his

own dictum of "reproducing prima facie the natives' own classification and nomenclature."

Furthermore he had downgraded kukwanebu or folk tales, missing one of their important

purposes, and has not recognized that many narratives are interstitial between 'folktale' and

'myth', hence are hard for Trobrianders to classify, and that particular narratives can be 'myth'

for children but 'folk tales' for adults (p. 50)

Malinowski asserts that his definitions of genre reflected Trobriand categories, which in turn were applied consistently by them. Leach points out that Malinowski modified these definitions over the course of his writing career while delineating what Leach found to be overly rigid boundaries. [5]

Utterances from the Past:

Trobrianders value the pronouncements of their ancestoras well as accounts of their activities. Libogwo include histories as well as the very important sub-category of lili’u (myth), which Malinowski stressed was ‘.... a reality lived.’ (1926b p. 100) He further states that, though both are regarded as true, the supernatural content of lili’u make the former easily recognizable from historical facts to all Trobrianders. [6]

A .... distinctive mark of the world of liliu lies in the super‑normal, supernatural character

of certain events which happen in it. The supernatural is believed to be true, and this truth

is sanctioned by tradition, and by the various signs and traces left behind by mythical

events, more especially by the magical powers handed on by the ancestors who lived in

times of liliu. This magical inheritance is no doubt the most palpable link between the

present and the mythical past. .... It is rather .... very much alive and true to the natives.

(1922 p. 303)

This begs the question as to whether the Trobrianders, who both believe in, as well as live, the reality of their myths, use the supernatural to distinguish myth from other forms of discourse. Certainly it cannot be the only characteristic for kukwanebu contain magical happenings such as a child nursing on its dead mother. (Leach, SN-8 & SN-40)

Leach indicates that most stories, not just myths, are thought to have originated in the past and divides these handed down texts into two types of narratives, collectively classed as livalela tomwaya (talking come down from the ancestors); these types are 1) liliu (myths) which are thought to have happened and 2) kukwanebu which are stories about things which did not happen. [7] (1981 p. 51) But Leach notes that livalela tomwaya also includes other types of talk, what Malinowski termed libogwo, ‘....such as decisions, the names of things and people, taboos and descriptions of things unseen. Livalela tomwaya therefore roughly approximates the notion 'our beliefs' or at least come closer than any other Kiriwinan category I know.’ (1981 50-51)

Leach notes that there are three types of liliu: libogwa, lirereni and livau, each employing li- as a prefix. Libogwa combines li- with -bogwa which refers to actions completed in the past while livau contains the vau suffix indicating new, newly or renewed. Livau are true narratives about people within living memory (Leach, 1981 p. 52) Montague perceptively explains that li- refers to source of things. Thus toliwaga, the term for the owner of a canoe, can be glossed as man (to-) source of (-li-) canoe (-waga), indicating his control of access to use of a canoe. Lili- in liliu can then be glossed as source of the source. (Personal Communication) Reduplication intensifies meaning and in this case points to the notion that myths are the ultimate source of knowledge about the past.

The importance of utterances from the past is reinforced by beliefs that the welfare of the living is directly in the hands of ‘those who spoke before’ and who take an active interest in the adherence to values laid down in the past by the living. Darrah (1972, 2011), Kasaipwalova (Malnic, 1996) and Mosko (2010 & personal communication) have argued that the baloma (spirits of the dead) are active agents in magic. It follows that Trobrianders emphasize the unaltered preservation of past utterances over the authorship of new ones.

In Myth in Primitive Psychology (p. 100), Sexual Lives (p. 453-4), Sex and Repression (p. 130) and finally in Coral Gardens (CGM p. 95-6) Malinowski interprets myth as a "charter of magical ritual and social order" thereby providing ‘.. a retrospective moral pattern of behavior. [8] (1926b p. 144),

Studied alive, myth is .... a narrative resurrection of a primeval reality, told in satisfaction

of deep religious wants, moral cravings, social submissions, assertions, even practical

requirements. Myth fulfills in primitive culture an indispensable function: it expresses,

enhances, and codifies belief; it safeguards and enforces morality; it vouches for the

efficiency of ritual and contains practical rules for the guidance of man. Myth is thus a

vital ingredient of human civilization; it is not an idle tale, but a hard‑worked active

force; it is not an intellectual explanation or an artistic imagery, but a pragmatic charter

of primitive faith and moral wisdom. (1926b p. 100)

Officially myths are narratives handed down unchanged from time immoral and as such are used to verify and adjudicate disputes over the ownership of important resources such as land and magic. (Hutchins, 1987) Some myths are essentially little more than lirereni. As described by Jerry Leach lirereni are ‘....narratives which revolve around an explicit pedigree or genealogy usually linking what someone has in the present, e.g. land, beach, reef, song, magic, tree, hamlet, or ornamentation rights, with a line of transmission back to their origin.’ (1981 p 53) Lirereni are owned having been previously exchanged for resources or services through pokola; they are also complex, containing a wealth of detail, and are seldom heard in public making them difficult to acquire as well. Despite claims to their immutability to the contrary, their semi-secret nature makes them amenable to twists and fabrications that serve the reciter’s own interests.

Change and the Immutable:

Trobrianders ideology about immutability of past expressions can be contrasted with Malinowski’s observations on elements of change in spell (yopa) compositions:

.... each spell shows unmistakable signs of being a collection of linguistic additions from

different epochs. There is in practically every one of them a good deal of archaic

material, but not a single one bears the stamp of having come down to us in the same

form in which it must have presented itself a few generations ago. So that it may be said

that a spell is constantly being remolded as it passes through the chain of magicians, each

probably leaving his mark, however small, upon it. (1922 p. 428-29)

Elsewhere Malinowski suggests that variations in spell content occur primarily in the middle part (tapwana) of the spell. Customarily spells start with a u’ula which consists of a lirereni (list) of the spell’s former owners extending back to the ancestor who brought the spell from the underworld. Malinowski notes that this portion of the spell, representing the most sacred part, is rendered with the greatest care and exactitude. (1935 II p. 258) ‘.... the u'ula begins with archaic, condensed compounds each carrying a self‑contained cycle of magical meaning. Then follows a list of forbears; then more explicit and, at the same time more dramatic sentences; an invocation to ancestral spirits ....’ (1922 p. 436) Magical formulae, and the u’ula in particular are full of loan words from other languages and metaphors which are unintelligible to the layman and sometimes even the magician. (Senft 1997 p. 370 & 2010 p. 40) In contrast the second part of the spell, the tapwana, is much more detailed and explicit employing a great deal of repetition laden with terms from everyday language.

It is Senft’s contention that biga baloma (speech of the ancestors) forms of expression, such as harvest songs (wosi milamala), which are dictated by the dead to living, and laden with esoteric meaning, channel... emotions bonding together members of a community united in mourning while preserving norms and other important aspects of Trobriand culture. Understanding of these forms is fading away. (Senft, 2009 p. 92 & 95) According to Senft esoteric words ‘.... serve the function of sociolinguistic variables which indicate high status of the speaker.’ (Senft, 2010 p. 11) He further indicates that since the mid nineteen eighties, Trobriand youth, under the influence of Christianity, are not investing the time and resources to purchase and learn spells from elders; as a result the social stature, as well as the economic welfare, of those who know the old ways have been diminished. (1997, p. 370)

Hard Words:

In Trobriand discourse ambiguity is believed to be essential to an individual’s survival giving rise to an interesting perspective on truth. Weiner has written extensively about the limits of Trobriand verbal expressions noting the degree of circumspection and compromise required to avoid confrontations which might lead individuals to employee sorcery in retaliation for open expression of words that offend. In everyday interactions people employee evasion as diplomacy:

In the Trobriand case, special attention is placed on the circumscription of the 'mind'

(nanola) as the area to which no‑one has access. Speaking what one truly thinks about

something is called 'hard words' (biga peula). Even though the truth about something

may be known to everyone, speaking the truth publicly exposes all the compromises and

negotiations under which individuals operate in their daily lives. For this reason,

saying 'hard words' is perceived to be extremely dangerous and produces immediate and

often violent repercussions. 'Hard words' once spoken cannot be recalled; apologies do not

carry any power to mute their effects. From this perspective, 'hard words' are weighty,

with the ability to penetrate the personal space of others. (Weiner, 1984b, p 693)

Senft notes that magic eschews this ambiguity employing biga peula that ‘.... inevitably demands action that, for either party involved in such a speech event, may be dangerous or even fatal.’ (2010 p. 46)

Sopa: Lies and Tricks

Some Trobriand stories of the kukwanebu variety feature a trickster’s masteryof a form of dissembling called sopa. Senft suggests that speech of the sopa variety gives rise to ambiguity that not only serves as a social lubricant but lends itself to playfulness :

We can translate sopa as "joke; lie; trick; something one does not really mean." ..... Both

vagueness and ambiguity are used by the speaker as a stylistic means to avoid possible

distress, confrontation and too aggressive directness in certain speech situations. It also

opens room and space where behaviour can be tried out playfully without any fear of

possible social sanctions ‑ because the speaker can always recede from what he has said

by labeling it as sopa, as something he did not really mean to say. (Senft, 1985b p. 427)

Forced to hide their true feelings people can make a virtue of the capacity to compose and pass off a clever deceit. Senft notes that sopa do not have the negative moral connotations that lies do in the West:

... Trobriand Islanders see them more as 'tricks' and means of 'tricking' ‑ and such a

behaviour is not necessarily socially sanctioned ‑ at least in ordinary everyday

interactions. Good and clever 'tricksters' can even be admired in certain situations and

their behaviour may give them even social status within the community. (2010, p. 152)

It should be noted here that valued forms of magic, such as love and beauty magic (mwasila), are designed to soften up people’s minds so that they accept sopa as reality. The old and ugly are thereby made young and beautiful. The great folk hero Tudava’s victory over his cannibal nemesis is accomplished with the aid of his mother’s magic which befuddles the cannibal’s mind to the point where he eats his own limbs thinking they belong to Tudava. (Leach SN-1, Baldwin,1971 p. 335-359)

Hard Jokes:

Hard words find their way into funny stories in recondite form. Gardner notes that kukwanebu ‘...obliquely denote the moral ambiguities of daily life, expressing sentiment one dare not say out loud. (1997) Vinavina (ditties), largely overlooked by other scholars, are a form of expression mastered by teenage girls that allows them to express the ‘inexpressible’. [9] Baldwin gives them serious treatment without referring to their usual dependence on ribald humor:

Another essential part of the Boyowan story is the poetic quotation, the Vinavina or ditty.

In the presence of strangers this element may be suppressed; yet it is to the story very

much what the u’ula or foundation is to the magic spell or the chorus to the song. It

comes into the story like a classical quotation or a proverb. Being in the language of

poetry it is well loaded with meaning and is sometimes quite cryptic.[10] If the story is

less familiar the elders crane their necks to hear the Vinavina. It is often sung and acted out.

Though it is avowedly recondite the story teller depends on it for full understanding and

sympathy. If the Vinavina would not be understood the story would seem to him, in the

absence of children, not worth the telling. (Baldwin 1971 p. 10)

Malinowski notes that a vinavina, which equates sexual intercourse with the planting of yams was, though not regarded as magic per see, thought to have a beneficial effect on the gardens. (1935 II, p. 135-6) They contain joking references to imaginary intercourse in the garden which stand in contrast to the deleterious effects of breaking the taboo against sex in the garden. As in the case with kukwanebu, to which a vinavina is often coupled, talk laden with sexual expressions is thought to be good for the growth of yams. In another example of tackling taboo with humor, young girls chant a vinavina about betel consumption which mentions ‘your mother licking your father's spatula’. (Senft, 2010 p. 240) This is playing with the ban against open expressions about a married couples sexual practices. As noted by Malinowski ‘The Trobriander's grossest and most unpardonable form of swearing or insult is Kwoy um kwava (copulate with thy wife). It leads to murder, sorcery, or suicide.’ (1929a, p. 93-4)

Kukwanebu:

Evasive speech is often missing in kukwanebu. As one reads the stories in the Baldwin and Leach collections one finds an abundance of open offensive verbal expressions in addition to ample examples of duplicity and mendacity, suggesting that one of the delights of these accounts is the freedom of expression enjoyed by the characters in these narratives. For example, in the story of Siligadoi (Leach SN-129), the hero, when accosted by a woman who obviously is a witch, unabashedly remarks on the exaggerated size, heat, and redness of her sexual organs before throwing caution to wind and engaging in terminal intercourse with her. Again, in Baldwin’s version of the Vinaya story, the heroine rejects suitors telling them to their face that they have are ugly. (Baldwin, 1971 p. 232)

According to Malinowski kukwanebu are humorous stories orfairy tales often ribald in nature with sex as a motif. (1929a p. 358) Leach points out that Malinowski contradicts himself as to whether folk tales (kukwanebu) are purely entertainment incorrectly indicated that these type of stories are owned, and that their performance was restricted to a particular season.

Kukwanebu are told when garden work is interrupted by the rains; however if told during times when play (masawa) is forbidden, i.e. times devoted to garden work such as weeding, during kula, or mourning, then they have a negative effect on the activity at hand. (Leach,1981 p. 51) Malinowski also notes there is some beliefs that recitation of these stories, about the foibles of human reproduction, have a positive magical influence on the recently planted yams. Kukwanebu are often ended with a challenge for a particular member of the audience to follow with his/her own story. The formula for this exchange, called katulogusa, is as follows:

"The kasiyena yams are breaking forth in clusters; this is the season when crops cut

through, when they grow round. I am cooking taro pudding; So‑and‑so (some important

person present is named in a jocular tone) will eat it. I shall break off betel‑nut; So‑and‑so

(another notable is named here) will eat it. Thy return payment, So‑and‑so (and the man

to recite next is named)." (1935 II, p 156-7)

It is said that the telling of kukwanebu excites the wild kasiyena yam to break forth in clusters of young yams which then causes the newly formed yams in the garden to mature. It is interesting to note that wild yams are also offered to the baloma ancestors at the inauguration of the new garden cycle when rituals call for their help in producing an abundant crop. Darrah (1972), Brindley (1984), and others have pointed to Trobrianders inclination for conflating the life cycles of humans and yams. In particular the ideology of asexual human reproduction mirrors that of yams. Garden rituals are replete with metaphorical elaborations of this theme. Thus the enceinte yams growing in the belly of the garden are aided by tales of human sexual exploits. The logic would be that young yams are metaphorical human babies. Human babies are fed semen which aids growth, so stories about human activities which produce semen cause yams to grow.[11]

The Baldwin and Leach collections contain a number of stores about hidden children living wild in the jungle for various reasons. These children generally prove to be beautiful and highly desirable; they are drawn into society by the milamala (harvest) dances[12] and end up marrying a person of rank. (SN 8, 40, 45, 162, 231) Naributal’s rendition of the Gilabwala story is an excellent example of this form. (Malnic, Gilabwala) In some cases the isolation is for the protection of a non-human mother, such as an octopus, who would be eaten if exposed human society.[13] (Montague, 1983 p. 4-8) Tudava, his mother abandoned by her brothers, and hiding from a cannibal, lived in enforced isolation, until he kills the cannibal, imposes his will upon his kin and marries his mother’s brother’s daughter. Living in isolation is strongly associated with anti-social activities such as sorcery. Montague reports Trobrianders tend to interpret westerner’s desire for solitude as evidence of a criminal past. (1989 p. 25) Baldwin notes a ‘... natural scorn and condemnation of those who lurk, even casually, in secret places is spontaneous and strong. Openness is so universally and assiduously cultivated that there is almost no privacy. (Baldwin, 1971 p. 26) Yet in folk tales the anti-social isolation becomes protective device of the individual suggesting that living with people, particularly with one’s kin, can be very dangerous.[14]

Conclusion:

Leach reminds us that stories both entertain and teach us as we enjoy their performances. ‘Folktales often carry implicit messages about social life which are seen to be serious and significant even if cloaked in playful clothing.’ (Leach,1981 P. 53) It goes without saying that students of the Trobriands can learn much from these stories. After all the naked truth is a rarity in the Trobriand context requiring one to hone their skills at seeing below the surface; these stories, designed to teach children about hidden truths, can teach us much as well.

Endnote:

Mythical Incest Revisited

Malinowski notes that men frequently dream of incest which suggests that their sisters are trying to seduce them since dreams are a sign that someone else’s love magic is working on their minds. Sisters try to seduce their brothers into raising yams for them and the two siblings should have a close relationship but these dreams may be a sign that the sister has stepped over the line.

Normally when a man dreams of a woman it is a sign that she has practiced love magic on him and wants him to pursue her. The man will feel ashamed and haunted when he dreams incestuously of his sister. However, Malinowski notes that brother/sister incest is very rare and when discovered would lead to the participants committing suicide out of shame.

. A family consisting of mother, son and daughter are engaged in routine

daily activities. The woman is cooking. The son has boiled coconut meat to

make oil over which he has said his beauty magic; he stores the gourd, with

the magical oil in his hut above the door. He then goes to the beach to fish.

. Later the sister decides to collect water and asks her mother where her

water bottles are. Absentmindedly the mother says they are in the boys’

hut---- a place completely off limit to the sister. The sister goes after the

bottles and a drop of the oil of beauty magic falls into her hair. Immediately

she feels an overriding desire for her brother and goes out to ask her mother

where the brother is. The mother responds he is fishing on the beach.

. The sister runs to the beach, sees her brother and strips off her skirt to pursue

him. He runs away but eventually succumbs to her advances and makes love to her.

They camp of the beach frequently making love until they eventually starve to death.

Out of their bones grows a sweetly scented mint plant.

. A man living on another island dreams about what has happened and he goes

to the young lover’s beach. He collects the mint plant which he uses as the basis

of what is to become the most potent form of love magic.

Analysis:

To fully appreciate this myth one must first put it into the context of Trobriand culture.

. There is a strong incest taboo among Trobrianders and the mother’s carelessness sets the tragedy in motion. She should have fetched the water bottles.

. The myth is laden with reproductive symbolism. Coconut oil is metaphorical seamen. A woman’s hair is the sight of conception. Trobrianders believe that women become pregnant, not as a result of intercourse but when one of her ancestor spirits, called a baloma, brings a spirit fetus (waiwaia) and places it in her hair. Eventually the waiwaia moves down her body and enters her womb. Water bottles are also connected to fertility because to induce pregnancy a family member will sometimes gather sea water in one and put it by the woman’s head as she sleeps. The belief being that waiwaia float on the sea and can be collected up for this purpose.

. The couple starves to death because in Trobriand custom sexual liaisons eventually lead to marriage. Marriage is formalized by family members bringing food (urigubu) to the couple who cannot eat until it is brought to them. Trobrianders say that a man and his family cannot eat the food (yams) that he has raised himself; rather the wife’s father and brother are supposed to provide a couple with their food. But this incestuous coupling cannot lead to marriage; the brother cannot feed himself, resulting in the couples starving to death.

. The mint plant which grows out of the couples bones is also highly symbolic and laden with meaning. A key metaphor in Trobriand thought is that men and yams are the same; one of their great culture heroes substitutes yams for men thereby abolishing cannibalism. In Trobriand mortuary and gardening rituals yam tubers and bones are analogous. The mint plant, unlike the yam vine, does not produce edible tubers which sustain life, just as a union between a brother and sister does not produce a gift of urigubu yams. Desire, induced by magic, is all well and good, and can attract people together, but it is only within the context of a community, which exchanges gifts, that individuals and relationships can survive.

-----------------

Reference Notes

I am concerned in this study to rescue the term Boyowa, which is the name of the main

island including its long tail. Kiriwina is the name of one of ten clusters of village

communities in the central group of islands, a name more softly pronounced by the

people who live there as Kilivila ..... The natural extension to cover the more populous

part of the island was always accepted from outsiders, but in recent times this has been

forced more and more on the local inhabitants and it is confusing. (1971 p. 28)

Senft prefers Kilivila over Boyowan calling the later term old. (2011 p. 43)

[2] Important contributions have been made by Gunter Senft, especially his recent Trobriand Islanders' Ways of Speaking, which classifies speech acts and offers numerous examples of various forms of Boyowan narratives. In Tuma Underworld of Love he also provides a goodly number of Wosi Milamala (songs of the harvest season) with a modicum of interpretation. Giancarlo Scoditti’s Kitawa Oral Poetry offers a wealth of spells and songs accompanied by extensive hermeneutics, although Senft is critical of Scoditti’s failure to classify the genre of each item. Edwin Hutchins’ Myth and Experience in the Trobriand Islands provides a variation and extensive analysis of the central myth which explains how it was that the dead became invisible to the living.

[3] Copies of Baldwin’s manuscript, Dokinikani: Cannibal Tales of the Wild Western Pacific, and as well as the transcriptions of performances were obtained at the Mission of the Sacred Heart Archives in Kensington, Australia through the good offices of Father Tony Caruana MSC, Provincial Archivist.

[4] Leach reports that the taped session, largely in villages on the north end of Kiriwina, during 1970-71. The following year, funded by a grant from the University of Papua New Guinea, approximately ten Trobriand students transcribed and translated them. Leach donated the original tapes and translations to UPNG in 1973 but took copies with him which he later donated to Smithsonian. The PDFs offered on this web site were created from copies made by the staff of the Smithsonian for the DEPTH Project. Leach gave each story an accession number starting with SN1 and running through SN365. Unfortunately there are some gaps in the DEPTH holdings, six of the stories between SN1 and SN 290 are missing as well as SN291 onward. The missing items reportedly do not exist in the Smithsonian collections. Files of seventy one of the stories, typed by students of the CSUS Trobriand Seminar, have also been posted. (See Table of Contents for the Leach Collection)

[5] According to Leach, Malinowski contradicts himself as to whether kukwanebu are purely entertainment, incorrectly indicates that these types of stories are owned, and that their performance was restricted to a particular season. (1981 p.51 )

[6] Montague was told by people from Kaduwaga, her field site, that the events in myths had not necessarily ever happened, never-the-less even though fictions they represented undeniable truths. (Personal Communication)

[7] Thus in Leach’s categories, kukwanebu, which are accounts of events that did not happen, but never-the-less originated in the past, are included in ‘our beliefs’. Leach also relates that most of kukwanebu recorded by Malinowski were of a traditional form while new ones were being added to peoples’ repertoires indicating the category contains new as well as old stories. (1981 p. 52)

[8] Baldwin makes an interesting assertion that liliu supports the status quo by establishing rights (duties, tabus and privileges) while libogwa, which isassociated withrituals, monuments, protocol and the tribal tradition, has more ‘dynamic’ applications linked to peoples aspirations and idealism. (Baldwin,1971 p. 284)

[10] As is the case of u’ula some of the cryptic qualities of vinavina stem from use of old forms of language (Digim’Rina personal communication).

[11] This line of reasoning might lead people to think that the introduction of real semen in the garden would lead to yam growth but this is not the case. Intercourse in the garden is forbidden nominally because it would cause wild pigs to come and destroy the crops. In essence all play, whether sexual or not, is forbidden during gardening for people’s minds must be focused on work. One of the cautions of kukwanebu and lili'u is that human sexuality must be controlled least couples fuck themselves to death (kilimata). Love magic is the fruit of a mythical of brother sister incest. (See below for a discussion of Malinowski’s incest myth from Sexual Lives of Savages) Montague says that Trobrianders are concerned that uncontrolled sexual desires, the appropriate behavior for the dead living in Tuma, will lead people to fuck themselves to death. (1981, p. 22) This theme of terminal intercourse, growing out of too great an attraction, occurs in the Leach collection, (SN 50, 129 & 252) as well as Montague but is eschewed, not surprisingly in Father Baldwin’s collection.

[12] This is the time for the return of the spirits of the dead to the world of the living. These spirits include the waiwaia (spirit infants) seeking a womb through which to re-enter the world.

[13] In stories species become mutable; animals give birth to humans and vice versa. (SN 32, 45, 145) Humans also give birth to heavenly bodies, and forces of nature.